Antibiologism in antispe

CN: Animal Symbolism vs Animal Mythologies

A start to my argumentation:

Animals as symbols is a dangerous terrain to step on, since

1.) images are to be seen in contexts of concrete modes of usage and are never stand-alone, absolute “symbols”.

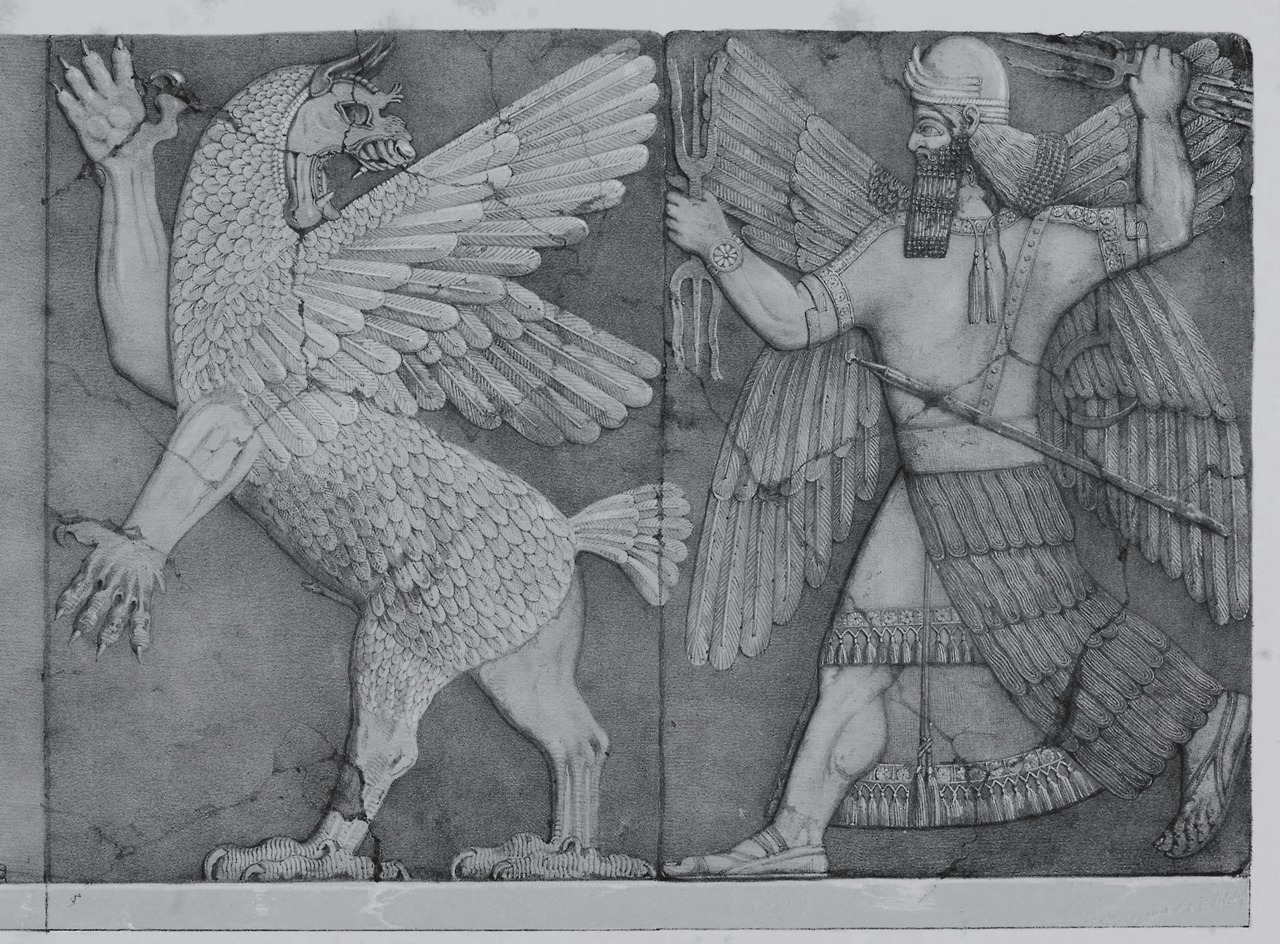

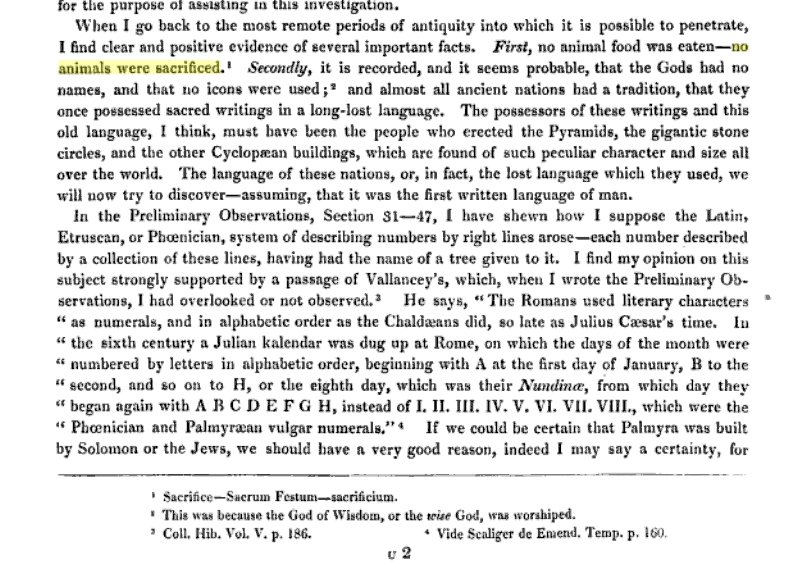

2.) When you have an epistemic background in which animals are mythological, they can never be reduced to symbols – or would you call deities or your god or your friend or ideals appearing anywhere to ever be just a “symbol”?

A symbol is a proxy for something else that it stands for. When it’s used to refer to real existent individuals you ethically enter a slippery slope, you start reducing the world to pictograms. Reducing the receptive interpretations of animal representations to “animal symbolism” fails to see the intricate languages expressed about human/animal relationships e.g. in arts but also in the iconographies of daily speciesism.

—

I wrote an English fragment on a difference between symbolism and mythology with this text: https://www.simorgh.de/objects/a-fragment-on-insect-mythologies/

I extended this draft in German here:

E-Reader: Gruppe Messel 2018 / 4. Jg. 1 (2018), Heft 4. ISSN 2700-6905, https://farangis.de/reader/e-reader_gruppe_messel_2018_4.pdf

And now I should translate my thoughts back to English. I will try to do this sometime hopefully soon … :

Ein Fragment über Insektenmythologien und Darstellungen von Insekten, und weshalb Erklärungen mittels Symbolismus nicht ausreichen um bestehende Korrelationen zu erklären

Soweit wir zu diesem Zeitpunkt herausfinden konnten, handeln die bekanntesten Mythologien über Insekten und ähnliche Invertebraten von: Bienen, Schmetterlingen, Spinnen, Skorpionen, Ameisen, Zikaden und den Skarabäus-Käfern … . Welches Ansehen welche Insekten wann genossen und warum, steht offen. In einigen Zeiten, Kulturen und Geographien wurden die Tiere oder einige Gruppen dieser, zumindest freundschaftlich, in anderen feindlich dargestellt. Insekten in Mythologien werden zumeist als ein Phänomen gedeutet, das sich primär über einen „Symbolismus“ erschließen soll. Es scheint, dass Autoren / Forscher meinen, es sei schwer vorstellbar, dass beispielsweise der Skarabäus (der im ägyptischen Pantheon dem Gott Kheper zugeordnet wurde), ein ‚Mistkäfer’ also, für mehr als allein das geschätzt wurde, was Menschen ihm, im Sinne ihrer eigenen anthropozentrischen Konzepte der Welt, derer Bedeutung und des Universums, zuschrieben. Was, wenn aber die frühen Ägypter beispielsweise eine Welt mit einem einzigartigen Wert im Leben und in den Aktivitäten der Skarabäus-Käfer gesehen hätten?

Es wäre doch möglich, dass es faszinierend war zu beobachten, wie die Käfer dieses Rund aus Erde und Dung gerollt haben, und dabei dahingehend Überlegungen anzustellen, welche Art des Sinnempfindens die Käfer der Existenz und dem Sein auf der Erde überhaupt selbst ‚lebten’. Tiere haben Vernunft, Tiere haben Sinn. Tiere denken. Vielleicht verfügten manche alten Zivilisationen und Kulturen noch über die Fähigkeit und über ein Interesse daran, nm-Tiere als tierliche Kulturen zu betrachten. Ein kleiner Käfer, der einen Ball gleich einem Planeten rollt, aus dem ein neues Insektenleben schlüpfen würde … . Das ist mehr als ein Symbol.

Ein typischer Gedanke, den man im Bezug auf nichtmenschliche Tiere und die Natur hinsichtlich von Mythologien antrifft, ist, dass Menschen der Natur immer nur im indirekten Sinne eine Bedeutung zugeordnet hätten. Menschen können aber doch auch gedacht und gefühlt haben, dass die Natur tatsächlich eine Bedeutung hatte, und dass Natur (und somit Existenz) überhaupt Bedeutung sei.

Zusätzlich sollte bedacht werden, dass wenn wir solch einer Beziehung in der Mythologie das Gewicht unserer heutigen Definition von „Symbolismus“ aufbürden wollen – das heißt wenn wir beispielsweise sagen, dass Insekten bloße Symbole anthropomorpher Attributisierungen gewesen seien – dann sollten wir doch immerhin die epistemologische Geschichte des „Symbols“ und die Etymologie dieses Begriffes näher betrachten, um Licht auf das Konstrukt zu werfen, von dem wir damit Gebrauch machen.

Interessant ist, dass selbst im Bezug auf unsere Gegenwart wir die Verwendung von Tierbildern in mehr oder weniger ähnlicher Weise deuten. Wir sehen das Tier als nicht viel mehr als einen Symbolismus.

Die Beziehung zur faktischen Gegenwart des ‚Tieres als Subjekt’, das unser sozialethisches Miteinander relevant werden ließe, spielt seitens des Künstlers sowie auch seitens des Betrachters für Kunstkritiker, Kunstwissenschaftler und Kunsthistoriker zumeist noch eine untergeordnete und eher indirekte Rolle, bei der in erster Linie die Subjektivität-des Menschlichen in Bezugnahme auf ‚das Menschliche‘ im Zirkelschlüssen zum Gegenstand des Sinnes von Kunst wird (und bleiben soll).

Der Bezug auf das dargestellte Tier und das Tierliche wird als indirekt gedeutet, auch wenn ein direkter Bezug intentioniert oder zumindest auch mit enthalten ist. Die alleinige Direktheit, die zugelassen wird, ist die objektifizierte und objektifizierende Haltung zum nm-Tier und zum Tierlichen. Die Direktheit wird Instrumentalisiert. Die Tendenz zur Verzwecklichung bei Anthropomorphismen in Tierdarstellungen macht die Beziehung noch unsichtbarer. So können wir kaum mehr von einer Micky Maus auf eine echte Maus schließen, da hier die Maus in der Art Darstellung nur noch ein dem Menschen gefälliges Bild verkörpern soll. Der Bezug zum nm-Tier bleibt aber relevant, denn sonst hätte man ebenso eine nicht zoomorphe Gestalt wählen können als zentralen ästhetischen Bildnisfaktoren. Wir sollten uns die Beziehungen zwischen darstellenden und dargestellten Subjekten viel genauer und tiefgreifender betrachten.

—

Manchmal muss ‘Neues’ entstehen, in der Form, dass alte Ambiguitäten ihre Klärung finden können: So müssen wir heute klären, warum “Tier” aus menschlich-moralischem Erwägen über ‘Wert, Sinn, Freiheit, Würde … ‘ die Stellung eines Antagonismus (zum ‘menschlichen Ideal’) von herrschenden Mehrheiten humaner Kulturgebilde zugeordnet bekam.